Difference between revisions of "PARAMITAYANA AND MANTRAYANA - 5"

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| − | [[Mahayana]], the 'Great [[Spiritual]] Course', is known as the '[[spiritual]] course of [[Bodhisattvas]]' in order to distinguish it from the 'Lesser Course' or [[Hinayana]] with the two divisions, [[Sravakayana]] and [[Pratyekabuddhayana]], both of which are [[recognized]] by [[Mahayana]] as preliminary steps. [[Sravakayana]] is the [[spiritual]] course of those who 'listen' to the [[discourses]] of [[religious]] [[masters]], have to be told everything regarding what to do and what not to do, and are unable to find their way and attain their goal without that continuous guidance upon which they thoroughly depend. In the course of [[human]] [[development]] the [[Sravaka]] belongs to the infancy stage. [[Pratyekabuddhayana]] is the course of the self-reliant persons who by their [[own]] power want to go their way and reach their goal. They may be persons of the lone-wolf type, men of the common herd, or selective persons who carefully choose their company. The common [[characteristic]] of [[Sravakas]] and [[Pratyekabuddhas]] is their selfcentredness which is only mitigated by the circumstance that in following a certain [[discipline]] they may become living examples of how to pursue the aim of self-development and in this way have a mediate effect on | + | [[Mahayana]], the 'Great [[Spiritual]] Course', is known as the '[[spiritual]] course of [[Bodhisattvas]]' in order to distinguish it from the 'Lesser Course' or [[Hinayana]] with the two divisions, [[Sravakayana]] and [[Pratyekabuddhayana]], both of which are [[recognized]] by [[Mahayana]] as preliminary steps. [[Sravakayana]] is the [[spiritual]] course of those who 'listen' to the [[discourses]] of [[religious]] |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[masters]], have to be told everything regarding what to do and what not to do, and are unable to find their way and attain their goal without that continuous guidance upon which they thoroughly depend. In the course of [[human]] [[development]] the [[Sravaka]] belongs to the infancy stage. [[Pratyekabuddhayana]] is the course of the self-reliant persons who by their [[own]] power want to go their way and | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | reach their goal. They may be persons of the lone-wolf type, men of the common herd, or selective persons who carefully choose their company. The common [[characteristic]] of [[Sravakas]] and [[Pratyekabuddhas]] is their selfcentredness which is only mitigated by the circumstance that in following a certain [[discipline]] they may become living examples of how to pursue the aim of self-development and in this way have a mediate effect on | ||

[[society]]. | [[society]]. | ||

The [[spiritual]] course of the [[Bodhisattvas]] or of those who belong to the {{Wiki|superior}} type of man in the triple {{Wiki|classification}} of mankind and who have [[realized]] that the [[idea]] of man is never an image of fulfilment but merely a {{Wiki|stimulus}} to his [[desire]] to rise above himself, comprises two courses which closely intermingle and, indeed, are complementary to each other, [[Paramitayana]] and [[Mantrayana]]. | The [[spiritual]] course of the [[Bodhisattvas]] or of those who belong to the {{Wiki|superior}} type of man in the triple {{Wiki|classification}} of mankind and who have [[realized]] that the [[idea]] of man is never an image of fulfilment but merely a {{Wiki|stimulus}} to his [[desire]] to rise above himself, comprises two courses which closely intermingle and, indeed, are complementary to each other, [[Paramitayana]] and [[Mantrayana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Paramitayana]], as its [[name]] implies, emphasizes the practice of the '[[perfections]]' of liberality, [[ethics]] and manners, [[patience]], strenuousness, [[meditative concentration]], and [[intelligence]] as the function which apprehends [[no-thing-ness]]. The former five are subsumed under 'fitness of [[action]]' or the [[moral]] frame within which the sixth, [[intelligence]], operates as a discriminative and appreciative function. Precisely because of its | [[Paramitayana]], as its [[name]] implies, emphasizes the practice of the '[[perfections]]' of liberality, [[ethics]] and manners, [[patience]], strenuousness, [[meditative concentration]], and [[intelligence]] as the function which apprehends [[no-thing-ness]]. The former five are subsumed under 'fitness of [[action]]' or the [[moral]] frame within which the sixth, [[intelligence]], operates as a discriminative and appreciative function. Precisely because of its | ||

| Line 15: | Line 23: | ||

levels that the [[perfections]] can express themselves properly and do not degenerate into sentimentalities and affectations. Other, though less known, names for this aspect of [[Mahayana Buddhism]] are Lak$aQayana (course of [[philosophical]] [[investigation]]) and [[Hetuyana]] (course of [[spiritual training]] in which [[attention]] is centred on the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm in [[human experience]]). | levels that the [[perfections]] can express themselves properly and do not degenerate into sentimentalities and affectations. Other, though less known, names for this aspect of [[Mahayana Buddhism]] are Lak$aQayana (course of [[philosophical]] [[investigation]]) and [[Hetuyana]] (course of [[spiritual training]] in which [[attention]] is centred on the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm in [[human experience]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Mantrayana]] (its full [[name]] is Guhya-mantra-phala-vajra-yana) is variously called [[Guhyamantrayana]], [[Phalayana]], Upayayana, and [[Vajrayana]]. | [[Mantrayana]] (its full [[name]] is Guhya-mantra-phala-vajra-yana) is variously called [[Guhyamantrayana]], [[Phalayana]], Upayayana, and [[Vajrayana]]. | ||

| − | The term [[Vajrayana]] has become the common [[name]] for this aspect of [[Mahayana Buddhism]] which has been misrepresented grossly by writers of different professions, mostly for two [[reasons]]. The first is plain [[ignorance]]. The [[Vajrayana]] texts deal with [[inner experiences]] and their [[language]] is highly symbolical. These [[symbols]] must be understood as [[symbols]] for the peculiar kind of [[experience]] which brought forth the peculiar [[verbal]] response, not for things which adequately (and even exhaustively) can be referred to by the literal [[language]] of everyday [[life]]. The [[symbols]] of [[Vajrayana]] do not stand literally for anything, they are meant as a help uto lead [[people]] to, and finally to evoke within them, certain [[experiences]] which those who have had them consider to be the most worth-while of all [[experiences]] available to [[human beings]]" 1. In brief, the [[language]] of [[Vajrayana]] is [[mystical]] and although it has an [[essentially]] material [[element]] in it, its [[intention]] is never material. The second [[reason]] for gross misrepresentation is that writers about [[Vajrayana]] have already made up their | + | |

| + | |||

| + | The term [[Vajrayana]] has become the common [[name]] for this aspect of [[Mahayana Buddhism]] which has been misrepresented grossly by writers of different professions, mostly for two [[reasons]]. The first is plain [[ignorance]]. The [[Vajrayana]] texts deal with [[inner experiences]] and their [[language]] is highly symbolical. These [[symbols]] must be understood as [[symbols]] for the peculiar kind of | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[experience]] which brought forth the peculiar [[verbal]] response, not for things which adequately (and even exhaustively) can be referred to by the literal [[language]] of everyday [[life]]. The [[symbols]] of [[Vajrayana]] do not stand literally for anything, they are meant as a help uto lead [[people]] to, and finally to evoke within them, certain [[experiences]] which those who have had them consider to be the | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | most worth-while of all [[experiences]] available to [[human beings]]" 1. In brief, the [[language]] of [[Vajrayana]] is [[mystical]] and although it has an [[essentially]] material [[element]] in it, its [[intention]] is never material. The second [[reason]] for gross misrepresentation is that writers about [[Vajrayana]] have already made up their | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[minds]] about the [[nature]] of [[Buddhism]]. This [[attitude]] has its [[root]] in the peculiar outlook that developed in the [[West]] after the {{Wiki|Middle Ages}}. There was, here, a progressive {{Wiki|emphasis}} upon [[knowledge]] which was born from | [[minds]] about the [[nature]] of [[Buddhism]]. This [[attitude]] has its [[root]] in the peculiar outlook that developed in the [[West]] after the {{Wiki|Middle Ages}}. There was, here, a progressive {{Wiki|emphasis}} upon [[knowledge]] which was born from | ||

| + | |||

the [[desire]] to achieve control over [[nature]] together with a possible [[transformation]] of {{Wiki|cultural}} patterns. Such a knowledge-norm does not take kindly to accepting and appreciating different {{Wiki|cultural}} [[forms]] or different premises of [[thought]] in their [[own]] right. It automatically will fit any | the [[desire]] to achieve control over [[nature]] together with a possible [[transformation]] of {{Wiki|cultural}} patterns. Such a knowledge-norm does not take kindly to accepting and appreciating different {{Wiki|cultural}} [[forms]] or different premises of [[thought]] in their [[own]] right. It automatically will fit any | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

1 John Hospers, Introduction to [[Philosophical]] Analysis. [[London]], Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. 1956, p. 374· | 1 John Hospers, Introduction to [[Philosophical]] Analysis. [[London]], Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. 1956, p. 374· | ||

| + | |||

{{Wiki|factual}} [[information]] about something alien to it into its preconceived schemata. As a {{Wiki|matter}} of fact, that which is to be considered as {{Wiki|factual}} or [[objective]]' (or whatever revised version of this now threadbare {{Wiki|abstraction}} may be brought forward) is already a selection from the vast amount of {{Wiki|data}} that eventually will be made to suit the [[existing]] pattern. Everything else is pushed into the background or dismissed as not being relevant ; otherwise it remains unintelligible why patently absurd theories should be perpetuated 1. | {{Wiki|factual}} [[information]] about something alien to it into its preconceived schemata. As a {{Wiki|matter}} of fact, that which is to be considered as {{Wiki|factual}} or [[objective]]' (or whatever revised version of this now threadbare {{Wiki|abstraction}} may be brought forward) is already a selection from the vast amount of {{Wiki|data}} that eventually will be made to suit the [[existing]] pattern. Everything else is pushed into the background or dismissed as not being relevant ; otherwise it remains unintelligible why patently absurd theories should be perpetuated 1. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

The long, though unwieldy, term Guhya-mantra-phala-vajra-yana can be translated as a course grounded in the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] {{Wiki|structure}} of the noetic as taking shape in active [[Buddhahood]], and which is the crowning result of a [[process of transformation]] that remains hidden to the ordinary | The long, though unwieldy, term Guhya-mantra-phala-vajra-yana can be translated as a course grounded in the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] {{Wiki|structure}} of the noetic as taking shape in active [[Buddhahood]], and which is the crowning result of a [[process of transformation]] that remains hidden to the ordinary | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

observer'. It points to every feature peculiar to this aspect of [[Mahayana]]. Its meaning has been given by [[Tsong-kha-pa]] as follows 2 : | observer'. It points to every feature peculiar to this aspect of [[Mahayana]]. Its meaning has been given by [[Tsong-kha-pa]] as follows 2 : | ||

((Since it is hidden and concealed and not an [[object]] for those who are not fit for it, it is secret' ([[gsang-ba]], [[guhya]]). | ((Since it is hidden and concealed and not an [[object]] for those who are not fit for it, it is secret' ([[gsang-ba]], [[guhya]]). | ||

((The {{Wiki|etymology}} of [[mantra]] is man {{Wiki|mentation}}' and tra [[protection]]', as laid down in the Guhyasamiijatantra (p. 156) 3 : | ((The {{Wiki|etymology}} of [[mantra]] is man {{Wiki|mentation}}' and tra [[protection]]', as laid down in the Guhyasamiijatantra (p. 156) 3 : | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Mentation which proceeds | Mentation which proceeds | ||

| Line 44: | Line 74: | ||

((Another explanation is that man refers to the [[awareness of reality]] as it is and tra to [[compassion]] protecting [[sentient beings]]. | ((Another explanation is that man refers to the [[awareness of reality]] as it is and tra to [[compassion]] protecting [[sentient beings]]. | ||

| − | 1 Closely connected with this peculiar outlook is the [[traditional]] [[religious]] background of the [[West]]. It took over from the Semitic {{Wiki|conception}} the story of the Fall of Man and this {{Wiki|Biblical}} tale underlies openly or covertly all accounts about the history of the [[development]] of [[Buddhist]] [[thought]]. Inasmuch as {{Wiki|erotic}} [[imagery]] is {{Wiki|taboo}} in the [[Western]] [[traditional]] [[religion]], this local [[belief]] is nevertheless made the basis for judging {{Wiki|cultural}} patterns that have a different premise and can be understood only from [[grasping]] them in their [[own]] right. [[Tantrism]] puts no premium or sanction on {{Wiki|sexual}} licence. Its [[moral]] code is about the strictest that can be demanded. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | 1 Closely connected with this peculiar outlook is the [[traditional]] [[religious]] background of the [[West]]. It took over from the Semitic {{Wiki|conception}} the story of the Fall of Man and this {{Wiki|Biblical}} tale underlies openly or covertly all accounts about the | ||

| + | |||

| + | history of the [[development]] of [[Buddhist]] [[thought]]. Inasmuch as {{Wiki|erotic}} [[imagery]] is {{Wiki|taboo}} in the [[Western]] [[traditional]] [[religion]], this local [[belief]] is nevertheless made the basis for judging {{Wiki|cultural}} patterns that have a different premise and can be understood only from [[grasping]] them in their [[own]] right. [[Tantrism]] puts no premium or sanction on {{Wiki|sexual}} licence. Its [[moral]] code is about the strictest that can be demanded. | ||

| + | |||

2 Tskhp III r2a seqq. | 2 Tskhp III r2a seqq. | ||

| Line 51: | Line 86: | ||

("Course' ([[theg-pa]], [[yana]]) is both goal-attainment or result, and goalapproach or causal situation, and since there is goal-directed {{Wiki|movement}}, one speaks of a 'course'. | ("Course' ([[theg-pa]], [[yana]]) is both goal-attainment or result, and goalapproach or causal situation, and since there is goal-directed {{Wiki|movement}}, one speaks of a 'course'. | ||

| − | (('Result' ('[[bras-bu]], [[phala]]) refers to the [[four purities]] of place, being, [[wealth]], and [[action]], i.e., the citadel of [[Buddhahood]], the Buddha-norms (of [[cognition]] and [[communication]]), the Buddha-riches, and the Buddhaactivities. When in anticipation of this goal one imagines oneself now as being engaged in the [[purification]] of the without and within by [[sacred]] utensils in the idst of [[gods]] (and [[goddesses]]) in a [[divine]] palatial mansion, one speaks of a [[Phalayana]] (a course which anticipates the goal), because one proceeds by a [[meditation]] which anticipates the result. Thus it is stated in the Bla-med-kyi rgyud-don-la 'jug-pa : 'Result -, because one proceeds by way of the purities of [[existence]], [[wealth]], place, and [[action]]'. | + | |

| − | ((The Vimalaprabhii states : '[[Vajra]] means [[sublime]] [[indivisibility]] and indestructibility, and since this is (the [[nature]] of) the course, one speaks of Vajraship'. This is to say that [[Vajrayana]] is the [[indivisibility]] of [[cause]] or [[Paramita]] method and effect or [[Mantra]] method. - According to the dBang mdor bstan : | + | |

| + | (('Result' ('[[bras-bu]], [[phala]]) refers to the [[four purities]] of place, being, [[wealth]], and [[action]], i.e., the citadel of [[Buddhahood]], the Buddha-norms (of [[cognition]] and [[communication]]), the Buddha-riches, and the Buddhaactivities. When in anticipation of this goal one imagines oneself now as being engaged in the [[purification]] of the without and within by [[sacred]] utensils in the idst | ||

| + | |||

| + | of [[gods]] (and [[goddesses]]) in a [[divine]] palatial mansion, one speaks of a [[Phalayana]] (a course which anticipates the goal), because one proceeds by a [[meditation]] which anticipates the result. Thus it is stated in the Bla-med-kyi rgyud-don-la 'jug-pa : 'Result -, because one proceeds by way of the purities of [[existence]], [[wealth]], place, and [[action]]'. | ||

| + | ((The Vimalaprabhii states : '[[Vajra]] means [[sublime]] [[indivisibility]] and indestructibility, and since this is (the [[nature]] of) | ||

| + | |||

| + | the course, one speaks of Vajraship'. This is to say that [[Vajrayana]] is the [[indivisibility]] of [[cause]] or [[Paramita]] method and effect or [[Mantra]] method. - According to the dBang mdor bstan : | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Awareness]] of [[no-thing-ness]] is the [[cause]]; To [[feel]] [[unchanging bliss]] is the effect. | [[Awareness]] of [[no-thing-ness]] is the [[cause]]; To [[feel]] [[unchanging bliss]] is the effect. | ||

The [[indivisibility]] of [[no-thing-ness]] | The [[indivisibility]] of [[no-thing-ness]] | ||

And [[bliss]] is known as the [[enlightenment]] of [[mind]]. | And [[bliss]] is known as the [[enlightenment]] of [[mind]]. | ||

| − | ((Here the [[indivisibility]] of [[awareness]] which directly intuits [[no-thingness]] and the [[unchanging]], [[supreme bliss]] is [[conceived]] as consisting of the two [[phenomena]] of goal-approach and goal-attainment. Such an [[interpretation]] of [[Vajrayana]], however, applies to the [[Anuttarayogatantras]], not to the three [[lower Tantras]], because, if this [[unchanging]], [[supreme bliss]] has to be effected by [[meditative practices]] preceding and [[including]] inspection, since it settles after the bliss-no-thing-ness [[concentration]] has been [[realized]], these causal factors are not {{Wiki|present}} in their entirety in the [[lower Tantras]]. Therefore, while this is correct for the general [[idea]] of [[Vajrayana]], it is not so for the {{Wiki|distinction}} in a causal situation course or in one anticipating the goal. For this [[reason]] the explanation of the sNy im-pa' i me-tog will have to be added: 'The [[essence]] of [[Mahayana]] is the [[six perfections]]; their [[essence]] is fitness of [[action]] and [[intelligence]] of which the [[essence]] or one-valueness is the [[enlightenment-mind]]. Since this it the Vajrasattva-concentration it is [[Vajra]], and being both [[Vajra]] and a [[spiritual]] course, one speaks of [[Vajrayana]]. And this is the meaning of | + | |

| + | |||

| + | ((Here the [[indivisibility]] of [[awareness]] which directly intuits [[no-thingness]] and the [[unchanging]], [[supreme bliss]] is [[conceived]] as consisting of the two [[phenomena]] of goal-approach and goal-attainment. Such an [[interpretation]] of [[Vajrayana]], however, applies to the [[Anuttarayogatantras]], not to the three [[lower Tantras]], because, if this [[unchanging]], [[supreme bliss]] has | ||

| + | |||

| + | to be effected by [[meditative practices]] preceding and [[including]] inspection, since it settles after the bliss-no-thing-ness [[concentration]] has been [[realized]], these causal factors are not {{Wiki|present}} in their entirety in the [[lower Tantras]]. Therefore, while this is correct for the general [[idea]] of [[Vajrayana]], it is not so for the {{Wiki|distinction}} in a causal situation | ||

| + | |||

| + | course or in one anticipating the goal. For this [[reason]] the explanation of the sNy im-pa' i me-tog will have to be added: 'The [[essence]] of [[Mahayana]] is the [[six perfections]]; their [[essence]] is fitness of [[action]] and [[intelligence]] of which the | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[essence]] or one-valueness is the [[enlightenment-mind]]. Since this it the Vajrasattva-concentration it is [[Vajra]], and being both [[Vajra]] and a [[spiritual]] course, one speaks of [[Vajrayana]]. And this is the meaning of | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Mantra yoga]]'. Thus [[Vajrayana]] is {{Wiki|synonymous}} with Vajrasattva-yoga which effects the indivisible union of fitness of [[action]] and [[intelligence]]. In it there are the two phases of a [[path]] and a goal. | [[Mantra yoga]]'. Thus [[Vajrayana]] is {{Wiki|synonymous}} with Vajrasattva-yoga which effects the indivisible union of fitness of [[action]] and [[intelligence]]. In it there are the two phases of a [[path]] and a goal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

'''Upayayana' (course of [[methods]]) means that the [[methods]] stressed in this course are {{Wiki|superior}} to those of the [[Paramitayana]]. As stated in the mTha' [[gnyis]] [[sel-ba]] : 'Because of [[indivisibility]], the goal being the [[path]], {{Wiki|superiority}} of [[methods]] and utter secrecy, one speaks of [[Vajrayana]], [[Phalayana]], Upayayana, and Guyha(mantra)yana respectively'". | '''Upayayana' (course of [[methods]]) means that the [[methods]] stressed in this course are {{Wiki|superior}} to those of the [[Paramitayana]]. As stated in the mTha' [[gnyis]] [[sel-ba]] : 'Because of [[indivisibility]], the goal being the [[path]], {{Wiki|superiority}} of [[methods]] and utter secrecy, one speaks of [[Vajrayana]], [[Phalayana]], Upayayana, and Guyha(mantra)yana respectively'". | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

This authoritative [[interpretation]] of the meaning of [[Paramitayana]] and [[Mantrayana]] needs only a few words by way of comment. [[Mantrayana]] certainly is a hidden and secret lore, not because something that is [[offensive]] has to be concealed, but because it is nothing tangibly concrete that one can display. It is something which relates to that which is most intimate: the refinement of the [[personality]], the [[cultivation]] of [[human]] values, the [[liberation]] of man from his bondage to things and, above all, | This authoritative [[interpretation]] of the meaning of [[Paramitayana]] and [[Mantrayana]] needs only a few words by way of comment. [[Mantrayana]] certainly is a hidden and secret lore, not because something that is [[offensive]] has to be concealed, but because it is nothing tangibly concrete that one can display. It is something which relates to that which is most intimate: the refinement of the [[personality]], the [[cultivation]] of [[human]] values, the [[liberation]] of man from his bondage to things and, above all, | ||

| − | from the mistaken and debasing [[idea]] that he himself is a thing, a narrowly circumscribed [[entity]] in a vast array of {{Wiki|impersonal}} and inhuman things. Certainly, a [[discipline]] which aims at preventing [[life]] from becoming a mere vegetative function and at rescuing man from being lost in an alldevouring, spiritless, unspirited, and inhuman {{Wiki|mass}}, is of no value to him whose only [[desire]] is to be led in such a way that he believes he is a leader. It is with regard to such [[people]] that [[Mantrayana]] has to be | + | |

| + | |||

| + | from the mistaken and debasing [[idea]] that he himself is a thing, a narrowly circumscribed [[entity]] in a vast array of {{Wiki|impersonal}} and inhuman things. Certainly, a [[discipline]] which aims at preventing [[life]] from becoming a mere vegetative | ||

| + | |||

| + | function and at rescuing man from being lost in an alldevouring, spiritless, unspirited, and inhuman {{Wiki|mass}}, is of no value to him whose only [[desire]] is to be led in such a way that he believes he is a leader. It is with regard to such [[people]] that [[Mantrayana]] has to be | ||

| + | |||

kept hidden and must never be divulged. A [[person]] who has not yet become fit and mature through having practised all that which is common to both Siitras and [[Tantras]] by following the [[graded path]] of the 'three types of man' - 'the [[person]] who is not a suitable receptacle for instruction', | kept hidden and must never be divulged. A [[person]] who has not yet become fit and mature through having practised all that which is common to both Siitras and [[Tantras]] by following the [[graded path]] of the 'three types of man' - 'the [[person]] who is not a suitable receptacle for instruction', | ||

| − | as the texts repeatedly refer to him-is unable to understand its significance and by his lack of [[understanding]] is merely courting {{Wiki|disaster}}. He will at once try to turn it into something which it never can be. Enmeshed in his {{Wiki|superstitions}} and goaded on by rash conclusions he will discount new and divergent [[insights]] as already long familiar, and he will level down the [[exceptional]] to the average (if not the below-average). For he hates to be forced to stand on his [[own]] feet ; after all it is so much easier and reassuring to find oneself supported by a prevailing opinion, even if it should be a most absurd one. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | as the texts repeatedly refer to him-is unable to understand its significance and by his lack of [[understanding]] is merely courting {{Wiki|disaster}}. He will at once try to turn it into something which it never can be. Enmeshed in his {{Wiki|superstitions}} and goaded on by rash conclusions he will discount new and divergent [[insights]] as already long familiar, and he will level down the [[exceptional]] to | ||

| + | |||

| + | the average (if not the below-average). For he hates to be forced to stand on his [[own]] feet ; after all it is so much easier and reassuring to find oneself supported by a prevailing opinion, even if it should be a most absurd one. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Every developmental process is something that occurs in the secret depths of man's being and that has to be guarded carefully against and protected from all that might interfere with it. This is done by remaining {{Wiki|aware}} of what is real. Therefore at every phase the contemplation of [[no-thing-ness]] is an inevitable accompaniment. Once this [[awareness]] is | Every developmental process is something that occurs in the secret depths of man's being and that has to be guarded carefully against and protected from all that might interfere with it. This is done by remaining {{Wiki|aware}} of what is real. Therefore at every phase the contemplation of [[no-thing-ness]] is an inevitable accompaniment. Once this [[awareness]] is | ||

| − | |||

| − | Being a course ([[yana]]) of [[transformation]] and transfiguration in which the goal determines the course, [[Mantrayana]] demands a different kind of [[thought]], which in the very act of [[thinking]] transforms me and in so doing brings me nearer to myself. This is not so much an [[achievement]] which, once it has been performed, can be labelled and shelved somewhere, because as a new {{Wiki|determinate}} and narrowly circumscribed [[state]] it would be as much a [[fetter]] as was the previous one. Rather, it remains a task which opens our [[eyes]] to new horizons. In other words, the goal is the project of myself as I am going to be when all bias due to direct and indirect indoctrination is abolished, and since our projects are not isolated events locked up inside a [[mind]], they refer to a whole [[world]] and its ordering. The goal, commonly referred to as [[Buddhahood]], is never a fixed {{Wiki|determinate}} [[essence]] ; it is a whole world-view. There is the 'citadel of [[Buddhahood]]' or the [[divine]] mansion which is not [[empty]] but lived in by '[[bodies]]' or more precisely by body-minds, which give this [[world]] its | + | |

| + | lost man glides off into uncertainty and becomes susceptible of error. Although in [[Buddhism]] error never implies culpability, it must be overcome because it is a straying away from an initial vividness and richness of [[experience]] into a bewildering [[state]] of {{Wiki|disintegration}} and [[dead]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]]. Such a necessary [[protection]] is [[offered]] by the [[mantra]] which, | ||

| + | |||

| + | as a {{Wiki|rule}}, is either decried as unintelligible gibberish or believed to possess [[occult powers]], all of which merely serves to mystify the issue. The [[mantra]], like the [[visualized]] images of [[gods]] and [[goddesses]], is a [[symbol]] which, precisely because it has no assigned connotation as has the literal sign we use in propositions, is capable of being understood in more significant ways, so that | ||

| + | |||

| + | its meanings are fraught with [[vital]] and [[sentient]] [[experience]]. The [[mantra]] opens a new avenue of [[thought]] which becomes truer to itself than does any other type of [[thinking]] which has found its limit in de-vitalized [[symbols]] or [[signs]] that can be used to signify anything without themselves being significant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Being a course ([[yana]]) of [[transformation]] and transfiguration in which the goal determines the course, [[Mantrayana]] demands a different kind of [[thought]], which in the very act of [[thinking]] transforms me and in so doing brings me nearer to myself. This is not so much an [[achievement]] which, once it has been performed, can be labelled and shelved somewhere, because as a new {{Wiki|determinate}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | and narrowly circumscribed [[state]] it would be as much a [[fetter]] as was the previous one. Rather, it remains a task which opens our [[eyes]] to new horizons. In other words, the goal is the project of myself as I am going to be when all bias due to direct and indirect indoctrination is abolished, and since our projects are not isolated events locked up inside a [[mind]], they refer to a whole [[world]] and | ||

| + | |||

| + | its ordering. The goal, commonly referred to as [[Buddhahood]], is never a fixed {{Wiki|determinate}} [[essence]] ; it is a whole world-view. There is the 'citadel of [[Buddhahood]]' or the [[divine]] mansion which is not [[empty]] but lived in by '[[bodies]]' or more precisely by body-minds, which give this [[world]] its | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[divine]] {{Wiki|status}} by reaching out to it by means of existentials, the norms of [[spirituality]], [[communication]], and [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] being in the [[world]]. There is the richness of [[communication]] as an act of {{Wiki|worship}} and lastly an enactment of [[Buddhahood]], the [[transformation]] and transfiguration of oneself and of the [[world]] in producing a new pattern that is more [[promising]] and more satisfying. Since one acts here in support of a goal as yet unrealized, this [[discipline]] is aptly called the course which makes the goal | [[divine]] {{Wiki|status}} by reaching out to it by means of existentials, the norms of [[spirituality]], [[communication]], and [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] being in the [[world]]. There is the richness of [[communication]] as an act of {{Wiki|worship}} and lastly an enactment of [[Buddhahood]], the [[transformation]] and transfiguration of oneself and of the [[world]] in producing a new pattern that is more [[promising]] and more satisfying. Since one acts here in support of a goal as yet unrealized, this [[discipline]] is aptly called the course which makes the goal | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

its base. This does not exclude its '[[cause]]', the [[Paramitayana]], which lays the foundation for an [[intellectual]] and [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|maturation}}. This enables man to acquire the values, ideals, and {{Wiki|principles}} with which he can create | its base. This does not exclude its '[[cause]]', the [[Paramitayana]], which lays the foundation for an [[intellectual]] and [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|maturation}}. This enables man to acquire the values, ideals, and {{Wiki|principles}} with which he can create | ||

| Line 79: | Line 163: | ||

futility of others. | futility of others. | ||

| − | The [[indivisibility]] of [[cause and effect]] is one of the many meanings of [[vajra]]. In this [[sense]] [[Vajrayana]] is {{Wiki|synonymous}} with [[Mantrayana]] and is the [[name]] for a technique or [[course of action]] which is controlled by the goal, the 'result' towards which the act is directed. In other words, the end controls the means, but the [[action]] is here and now, although the goal to · be reached is still at some 'place', the citadel of [[Buddhahood]] which in the [[pure]] [[Buddha-sphere]] is the Akani$tha-heaven and in the human-divine [[sphere]] the palatial mansion of the ma1J4ala, both of which are as yet [[undetermined]] in ordinary place and time. This is not purposive in the ordinary [[sense]] of the [[word]], it is an integrative process of a higher order. It leads to the second meaning of [[vajra]] and indicates the blending of [[action]] and [[insight]]. In {{Wiki|theory}}, we may separate [[awareness]] from [[action]], but as phases of our being they are closely [[interdependent]]. The more I understand myself as being a fixed [[entity]] the more degraded my [[actions]] become ; and, conversely, the less self-centred I become the less biased are my [[actions]] and relations with others. The unificatory process is named Vajrasattva-yoga. In [[Buddhism]], [[yoga]] never means to be swallowed up by an [[Absolute]], nor does it imply anything which {{Wiki|Occidental}} faddism fancies it to be ; it always means the union of 'fitness of [[action]]' and '[[intelligence]]'. In this process certain norms are revealed, which are always active and dynamic. They have become known by their [[Indian]] names, [[Dharmakaya]], [[Sambhogakaya]], and Nirma!).akaya, but never have been understood properly, within the framework of [[traditional]] [[Western]] [[semantics]], because of the essentialist premises of [[Western]] [[philosophies]]. [[Essence]] is that which marks a thing off and separates it from other entities of a different kind. From such a point of view all of man's [[actions]] spring from that which is considered to be his [[intrinsic nature]]. Its [[fallacy]] is that it makes us overlook man's relational being ; the actual [[person]] always [[lives]] in a [[world]] with others. And, in [[Wikipedia:Human life|human life]], [[essence]] tells man that he is already what he can be, so there is no need to set out on a [[path]] of [[spiritual development]]. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | The [[indivisibility]] of [[cause and effect]] is one of the many meanings of [[vajra]]. In this [[sense]] [[Vajrayana]] is {{Wiki|synonymous}} with [[Mantrayana]] and is the [[name]] for a technique or [[course of action]] which is controlled by the goal, the 'result' towards which the act is directed. In other words, the end controls the means, but the [[action]] is here and now, although the goal to · be reached is still at some 'place', the citadel of [[Buddhahood]] which in the [[pure]] [[Buddha-sphere]] is the Akani$tha-heaven | ||

| + | |||

| + | and in the human-divine [[sphere]] the palatial mansion of the ma1J4ala, both of which are as yet [[undetermined]] in ordinary place and time. This is not purposive in the ordinary [[sense]] of the [[word]], it is an integrative process of a higher order. It leads to the second meaning of [[vajra]] and indicates the blending of [[action]] and [[insight]]. In {{Wiki|theory}}, we may separate [[awareness]] from [[action]], but as phases of our being they are closely [[interdependent]]. The more I understand myself as being a fixed [[entity]] the | ||

| + | |||

| + | more degraded my [[actions]] become ; and, conversely, the less self-centred I become the less biased are my [[actions]] and relations with others. The unificatory process is named Vajrasattva-yoga. In [[Buddhism]], [[yoga]] never means to be swallowed up by an [[Absolute]], nor does it imply anything which {{Wiki|Occidental}} faddism fancies it to be ; it always means the union of 'fitness of [[action]]' and '[[intelligence]]'. In this process certain norms are revealed, which are always active and dynamic. They have become known by their | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Indian]] names, [[Dharmakaya]], [[Sambhogakaya]], and Nirma!).akaya, but never have been understood properly, within the framework of [[traditional]] [[Western]] [[semantics]], because of the essentialist premises of [[Western]] [[philosophies]]. [[Essence]] is that which marks a thing off and separates it from other entities of a different kind. From such a point of view all of man's [[actions]] spring from that which is considered to be his [[intrinsic nature]]. Its [[fallacy]] is that it makes us overlook man's relational being ; the actual | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[person]] always [[lives]] in a [[world]] with others. And, in [[Wikipedia:Human life|human life]], [[essence]] tells man that he is already what he can be, so there is no need to set out on a [[path]] of [[spiritual development]]. | ||

Seen as [[existential]] norms these three patterns reveal their significance. | Seen as [[existential]] norms these three patterns reveal their significance. | ||

| + | |||

[[Dharmakaya]] indicates the intentional {{Wiki|structure}} of the noetic in man. It is the [[merit]] of [[Buddhism]] that it has always [[recognized]] this feature of [[awareness]] : I cannot know without [[knowing]] something, just as I cannot do without doing something. But in [[ordinary knowledge]] whatever | [[Dharmakaya]] indicates the intentional {{Wiki|structure}} of the noetic in man. It is the [[merit]] of [[Buddhism]] that it has always [[recognized]] this feature of [[awareness]] : I cannot know without [[knowing]] something, just as I cannot do without doing something. But in [[ordinary knowledge]] whatever | ||

[[ss]] | [[ss]] | ||

| − | I know is overshadowed by [[beliefs]], presuppositions, likes and dislikes. However, the more I succeed in removing myself from self-centred concerns and situations and free myself from all bias, the more I am enabled to apprehend things as they are. This happens in [[disciplined]] [[philosophical]] enquiry through which one gradually approaches [[no-thingness]] and indeterminacy, from the vantage point of which one can achieve a view of [[reality]] without internal warping. This [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] indeterminacy which underlies .the whole noetic enterprise of man is richer in contents and broader in its horizons than any other [[awareness]] because it is an unrestricted {{Wiki|perspective}} from which nothing is screened or excluded. If anything can be predicated about it, it is [[pure]] [[potency]] which, when actualized, enables us to see ourselves and things as we and they really | + | |

| + | I know is overshadowed by [[beliefs]], presuppositions, likes and dislikes. However, the more I succeed in removing myself from self-centred concerns and situations and free myself from all bias, the more I am enabled to apprehend things as they are. This happens in [[disciplined]] [[philosophical]] enquiry through which one gradually approaches [[no-thingness]] and indeterminacy, from the vantage point | ||

| + | |||

| + | of which one can achieve a view of [[reality]] without internal warping. This [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] indeterminacy which underlies .the whole noetic enterprise of man is richer in contents and broader in its horizons than any other [[awareness]] because it is an unrestricted {{Wiki|perspective}} from which nothing is screened or excluded. If anything can be predicated about it, it is [[pure]] [[potency]] which, when actualized, enables us to see ourselves and things as we and they really | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

are. In order to gain this capacity we have to develop our [[intelligence]], our critical acumen, which is the main theme of the [[Paramitayana]] and without which [[Mantrayana]] is impossible. But all the [[information]] we receive through such sustained analysis is not merely for the [[sake]] of [[pure awareness]] or contemplation, but in order that we may act. Every | are. In order to gain this capacity we have to develop our [[intelligence]], our critical acumen, which is the main theme of the [[Paramitayana]] and without which [[Mantrayana]] is impossible. But all the [[information]] we receive through such sustained analysis is not merely for the [[sake]] of [[pure awareness]] or contemplation, but in order that we may act. Every | ||

| − | |||

| − | which we would term the Nirmal).akaya. This gives the clue to an [[understanding]] of this technical term which is left untranslated in works dealing with [[Buddhism]]. Nirmal).akaya {{Wiki|signifies}} being in the [[world]], not so much as a being among things and {{Wiki|artifacts}}, but as an active being in [[relation]] to a vast field of surrounding entities which are equally vibrating with [[life]], all of them ordered in a [[world]] {{Wiki|structure}}. As an active mode of being Nirmal).akaya is the implementation of man's whole being, the ordering of his [[world]] in the {{Wiki|light}} of his [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] possibilities. | + | |

| + | [[insight]] is barren if it does not find expression in [[action]], and every [[action]] is futile if it is not supported by [[sound]] [[insight]]. Only when we succeed in [[understanding]] ourselves, our projects and our [[world]] from a point of view which is no point of view, will a [[sound]] [[direction]] of [[human]] [[action]] be possible, because it is no longer subordinated to petty, self-centred concerns. This active mode of being is [[realized]] through the two operational patterns or norms, the [[Sambhogakaya]] and the | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nirmal).akaya, both of which have their raison d'etre in the cognitive-spiritual mode. Strictly {{Wiki|speaking}}, only the Nirmal).akaya is perceptible, although it would be wrong to assume that it is of a [[physical]] [[nature]]. As a {{Wiki|matter}} of fact, as [[ordinary beings]] we are unable to discern whether somebody [[embodies]] the Nirmal).akaya or not. Only at some later time, after centuries and generations may we come to realize that this [[person]] or that has been that | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | which we would term the Nirmal).akaya. This gives the clue to an [[understanding]] of this technical term which is left untranslated in works dealing with [[Buddhism]]. Nirmal).akaya {{Wiki|signifies}} being in the [[world]], not so much as a being among things and {{Wiki|artifacts}}, but as an active being in [[relation]] to a vast field of surrounding entities which are equally vibrating with | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[life]], all of them ordered in a [[world]] {{Wiki|structure}}. As an active mode of being Nirmal).akaya is the implementation of man's whole being, the ordering of his [[world]] in the {{Wiki|light}} of his [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] possibilities. | ||

In our everyday [[life]] we understand others, for the most part, from what they do, the functions they perform, and this appears to be a static | In our everyday [[life]] we understand others, for the most part, from what they do, the functions they perform, and this appears to be a static | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

and {{Wiki|impersonal}} order. Anyone may perform this function or that. The main thing is that business goes on. There is little scope for the NirmaI).akaya, because that would be something [[exceptional]], and the [[exceptional]] is at once levelled down to the average. However, the ordering of one's | and {{Wiki|impersonal}} order. Anyone may perform this function or that. The main thing is that business goes on. There is little scope for the NirmaI).akaya, because that would be something [[exceptional]], and the [[exceptional]] is at once levelled down to the average. However, the ordering of one's | ||

| − | [[life]] and of the [[world]] in which one [[lives]] is certainly not an {{Wiki|impersonal}} or depersonalized act. Man is never alone, but always reaches out to others. He does this through [[communication]]. Usually this happens in the verbosity of everyday chatter. The more words that are uttered the more there seems to have been said, and therefore some {{Wiki|modern}} [[philosophers]] think that a proper manipulation of {{Wiki|linguistic}} [[symbols]] will solve all problems of being. Just as a [[world]] of things cannot give meaning to man's being in the [[world]], the verbose [[discourse]] indulged in by various groups is unable to clarify man's being with others. [[Universal]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] and ready-made judgments are utterly inadequate. Real being with others must spring up on the spur of the [[moment]] and arouse us to our possibilities. That which does so is the [[Sambhogakaya]]. Grounded in unrestricted and unbiased [[cognition]] it can establish [[contact]] with others and stir them to [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] [[action]]. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | [[life]] and of the [[world]] in which one [[lives]] is certainly not an {{Wiki|impersonal}} or depersonalized act. Man is never alone, but always reaches out to others. He does this through [[communication]]. Usually this happens in the verbosity of everyday chatter. The more words that are uttered the more there seems to have been said, and therefore some {{Wiki|modern}} [[philosophers]] think that a proper | ||

| + | |||

| + | manipulation of {{Wiki|linguistic}} [[symbols]] will solve all problems of being. Just as a [[world]] of things cannot give meaning to man's being in the [[world]], the verbose [[discourse]] indulged in by various groups is unable to clarify man's being with others. [[Universal]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] and ready-made judgments are utterly inadequate. Real being with others must spring up on the spur of the [[moment]] and arouse us to our possibilities. That which does so is the [[Sambhogakaya]]. Grounded in unrestricted and unbiased | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[cognition]] it can establish [[contact]] with others and stir them to [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] [[action]]. | ||

The union of [[insight]] and [[action]], of [[unlimited]] [[cognition]] and its active framework of [[communication]] with others in a [[world]] order, is referred to by the [[symbol]] of [[Vajrasattva]] : (([[Vajra]] is the Dharmakayic [[awareness]] in which three types of [[enlightenment]] enter indivisibly from ultimateness, and [[Sattva]] is the apprehendable [[form]] pattern deriving from it" 1. The attempt to effect this {{Wiki|integration}} of [[thought]] and [[action]] is termed Vajrasattvayoga, which is {{Wiki|synonymous}} with [[Vajrayana]]. | The union of [[insight]] and [[action]], of [[unlimited]] [[cognition]] and its active framework of [[communication]] with others in a [[world]] order, is referred to by the [[symbol]] of [[Vajrasattva]] : (([[Vajra]] is the Dharmakayic [[awareness]] in which three types of [[enlightenment]] enter indivisibly from ultimateness, and [[Sattva]] is the apprehendable [[form]] pattern deriving from it" 1. The attempt to effect this {{Wiki|integration}} of [[thought]] and [[action]] is termed Vajrasattvayoga, which is {{Wiki|synonymous}} with [[Vajrayana]]. | ||

| − | |||

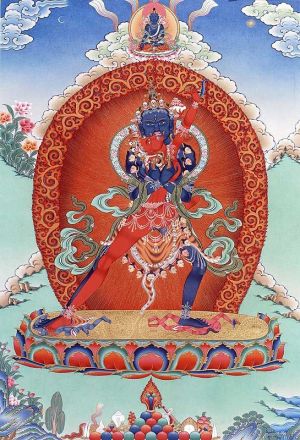

| − | our [[spiritual life]]. The same is true of {{Wiki|sexual}} [[love]] when it is fully [[human]]. The lover [[desires]] [[physical]] [[contact]], almost identification and assimilation of the beloved, which is one unique way in which a [[person]] can achieve closest [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|unity}} with another. The [[language]] of [[poetry]] and [[religion]] which expresses these things is [[mystic]] [[language]]. It has an [[essentially]] material [[element]] in it, but its [[intention]] is not finally material or it would be mere [[idolatry]] or [[sensuality]]. In our [[embodied]] [[experience]] the two aspects are so interfused that the [[language]] of {{Wiki|space and time}} and of | + | There is yet another meaning to [[Vajrasattva]], which is the central theme of the [[highest]] [[form]] of [[Mantrayana]], the [[Anuttarayogatantra]] or 'the continuity of the unificatory process which is [[unsurpassed]]'. This truly inward event is represented [[symbolically]] by two [[human]] [[bodies]] in intimate embrace. This is so because the [[human body]] is the easiest [[form]] in which we |

| + | |||

| + | can understand that which is most important to us, and the embrace is the most {{Wiki|intimate connection}} that can [[exist]] between two different persons. This seemingly {{Wiki|sexual}} [[symbolism]] has shocked many an observer who merely read his [[own]] pre-occupation with | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|sex}} into the [[symbol]] [[representation]] and completely failed to [[grasp]] the premises from which this [[symbolism]] sprang. L. A. Reid aptly remarks : ((There is [[mythic]] [[thinking]] here, and it is necessary. It is not the end or the last [[word]], but only one way in which we {{Wiki|physically}} bodied creatures can live intensely | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | our [[spiritual life]]. The same is true of {{Wiki|sexual}} [[love]] when it is fully [[human]]. The lover [[desires]] [[physical]] [[contact]], almost identification and assimilation of the beloved, which is one unique way in which a [[person]] can achieve closest [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|unity}} with another. The [[language]] of [[poetry]] and [[religion]] which expresses these things is [[mystic]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[language]]. It has an [[essentially]] material [[element]] in it, but its [[intention]] is not finally material or it would be mere [[idolatry]] or [[sensuality]]. In our [[embodied]] [[experience]] the two aspects are so interfused that the [[language]] of {{Wiki|space and time}} and of | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[actions]] therein is the [[language]] of the [[spirit]] as [[embodied]]" 1. Certainly, such [[symbol]] [[language]] and [[representation]] is more effective than to say abstractly that Va;'ra is the [[symbol]] for the noetic which is {{Wiki|present}} as an | [[actions]] therein is the [[language]] of the [[spirit]] as [[embodied]]" 1. Certainly, such [[symbol]] [[language]] and [[representation]] is more effective than to say abstractly that Va;'ra is the [[symbol]] for the noetic which is {{Wiki|present}} as an | ||

| − | {{Wiki|indeterminate}} relational [[form]], grounded in the [[knowing]] agent, and that [[Sattva]] is {{Wiki|determinate}} and has apparently its [[own]] ground, and that this [[duality]], which we encounter as the subject-object [[division]], is overcome when the {{Wiki|indeterminate}} relational [[form]] is terminated or filled by the [[object]] and thus becomes {{Wiki|determinate}}. It is cold {{Wiki|comfort}} to speak of [[Vajrasattva]] as the [[symbol]] of noetic [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]], where [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] is formal, not [[existential]] ; and this becomes still more uncomfortable when we consider it merely from a cognitive-intellectual aspect, because we have | + | |

| − | tended to separate [[feeling]] from [[knowing]] and to consider them as incompatible. In [[Buddhism]], [[knowing]] has a connotation of [[bliss]], while unknowing is [[suffering]]. This [[bliss]] reaches its [[highest]] pitch when [[knowledge]] becomes free, when nothing restricts the range of its possible terms. [[Cognition]] is thus commensurate with [[ecstasy]]. This [[experience]] is technically known as the '[[indivisibility]] of [[bliss]] and [[no-thing-ness]]' which Tsongkha-pa defines as follows : ((When the [[subjective]] pole or the noetic, which has become its existentially [[inherent]] [[bliss]], [[understands]] the [[objective]] pole or [[no-thing-ness]] without internal warping, this union of [[subject]] and [[object]] is the indivisible {{Wiki|unity}} of [[bliss]] and [[no-thing-ness]]" 2 . | + | |

| + | {{Wiki|indeterminate}} relational [[form]], grounded in the [[knowing]] agent, and that [[Sattva]] is {{Wiki|determinate}} and has apparently its [[own]] ground, and that this [[duality]], which we encounter as the subject-object [[division]], is overcome when the {{Wiki|indeterminate}} relational [[form]] is terminated or filled by the [[object]] and thus becomes {{Wiki|determinate}}. It is cold {{Wiki|comfort}} to speak of [[Vajrasattva]] as the [[symbol]] of noetic [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]], where | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] is formal, not [[existential]] ; and this becomes still more uncomfortable when we consider it merely from a cognitive-intellectual aspect, because we have | ||

| + | tended to separate [[feeling]] from [[knowing]] and to consider them as incompatible. In [[Buddhism]], [[knowing]] has a connotation of | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[bliss]], while unknowing is [[suffering]]. This [[bliss]] reaches its [[highest]] pitch when [[knowledge]] becomes free, when nothing restricts the range of its possible terms. [[Cognition]] is thus commensurate with [[ecstasy]]. This [[experience]] is technically known as | ||

| + | |||

| + | the '[[indivisibility]] of [[bliss]] and [[no-thing-ness]]' which Tsongkha-pa defines as follows : ((When the [[subjective]] pole or the noetic, which has become its existentially [[inherent]] [[bliss]], [[understands]] the [[objective]] pole or [[no-thing-ness]] without internal warping, this union of [[subject]] and [[object]] is the indivisible {{Wiki|unity}} of [[bliss]] and [[no-thing-ness]]" 2 . | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

The {{Wiki|recognition}} of [[existential]] categories as dynamic ways of being centres [[attention]] on how man acts rather than on what he is. The [[Sutras]], on which the [[Paramitayana]] bases its [[teaching]], give us a [[disciplined]] analy | The {{Wiki|recognition}} of [[existential]] categories as dynamic ways of being centres [[attention]] on how man acts rather than on what he is. The [[Sutras]], on which the [[Paramitayana]] bases its [[teaching]], give us a [[disciplined]] analy | ||

sis of man's [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] capacity, but they do not, or at least not with unmistakable clarity and distinctness, study the active modes by which this power realizes itself in ordering the [[world]] in which we live with others. Since we cannot live well with others unless we have first de- | sis of man's [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] capacity, but they do not, or at least not with unmistakable clarity and distinctness, study the active modes by which this power realizes itself in ordering the [[world]] in which we live with others. Since we cannot live well with others unless we have first de- | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

1 Ways of [[Knowledge]] and [[Experience]], p. 147· 2 Tskhp VII r, 55b . | 1 Ways of [[Knowledge]] and [[Experience]], p. 147· 2 Tskhp VII r, 55b . | ||

| − | veloped a decisive [[insight]] into our [[nature]] and our role in establishing a [[world]] order, the [[Sutras]] are a preliminary step in this [[direction]] as they [[concentrate]] on the [[development]] of the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] capacity which, when brought to utmost clarity, enables man to set out on the [[Mahayana path]]. Thus [[Mantrayana]] and [[Paramitayana]], contrary to the opinion of certain [[scholars]], are not two different and incompatible aspects of [[Buddhism]], but are complementary to each other because the one [[concentrates]] on the [[development]] of an unbiased outlook and an unrestricted {{Wiki|perspective}}, the other on the implementation of the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm through operational ones in [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] being with others and for others in a [[world]] that has been ordered in the {{Wiki|light}} of man's [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] and [[existential]] norms. This complementary [[character]] of [[Mantrayana]] and [[Paramitayana]] is clearly evident from [[Tsong-kha-pa's]] and other [[Tibetan]] [[sages]]' writings. [[Tsong-kha-pa's]] words are 1 : | + | |

| − | ''[[Buddhahood]], which fulfils the needs of others by [[manifesting]] itself to them, does not do so through the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm, the [[Dharmakaya]], but through the two operational ones, the [[Sambhogakaya]] and NirmaI).akaya. In this [[respect]] it is the [[philosophical]] conviction of all [[Mahayanists]] that the [[realization]] of the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm through {{Wiki|intelligent}} [[appreciative discrimination]] which intuitively apprehends the profound [[nature]] (or [[no-thing-ness]]) of all that is, that the [[realization]] of the two operational norms comes through unbounded [[activity]], and that [[insight]] and [[action]] must for ever work together because they are unable to effect anything if they are divorced from each other. [[Intelligence]] which apprehends the profound [[nature]] of all that is, is the same in [[Mantrayana]] as it is in the two lower courses ([[Hinayana]] and [[Paramitayana]]), because without [[understanding]] existentiality it is impossible to cross the ocean of Sarp.sara by | + | |

| − | exhausting our [[emotional]] reactions. Therefore, the special and prominent feature of the [[Mahayana path]] is the instrumentality of the two operational norms which [[manifest]] themselves to the prepared and serve as a protective guidance to [[sentient beings]] as long as Sarp.sara lasts. Although the followers of the [[Paramitayana]] attend to an inner course that corre | + | veloped a decisive [[insight]] into our [[nature]] and our role in establishing a [[world]] order, the [[Sutras]] are a preliminary step in this [[direction]] as they [[concentrate]] on the [[development]] of the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] capacity which, when brought to utmost clarity, enables man to set out on the [[Mahayana path]]. Thus [[Mantrayana]] and [[Paramitayana]], contrary to the opinion of |

| + | |||

| + | certain [[scholars]], are not two different and incompatible aspects of [[Buddhism]], but are complementary to each other because the one [[concentrates]] on the [[development]] of an unbiased outlook and an unrestricted {{Wiki|perspective}}, the other on the implementation of the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm through operational ones in [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] being with others and for others in a [[world]] that has been ordered in the {{Wiki|light}} of man's [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] and [[existential]] norms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This complementary [[character]] of [[Mantrayana]] and [[Paramitayana]] is clearly evident from [[Tsong-kha-pa's]] and other [[Tibetan]] [[sages]]' writings. [[Tsong-kha-pa's]] words are 1 : | ||

| + | ''[[Buddhahood]], which fulfils the needs of others by [[manifesting]] itself to them, does not do so through the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm, the [[Dharmakaya]], but through the two operational ones, the [[Sambhogakaya]] and NirmaI).akaya. In | ||

| + | |||

| + | this [[respect]] it is the [[philosophical]] conviction of all [[Mahayanists]] that the [[realization]] of the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm through {{Wiki|intelligent}} [[appreciative discrimination]] which intuitively apprehends the profound [[nature]] (or [[no-thing-ness]]) of all that is, that the [[realization]] of the two operational norms comes through unbounded [[activity]], and that [[insight]] and [[action]] must for ever work together because they are unable to effect anything if they are | ||

| + | |||

| + | divorced from each other. [[Intelligence]] which apprehends the profound [[nature]] of all that is, is the same in [[Mantrayana]] as it is in the two lower courses ([[Hinayana]] and [[Paramitayana]]), because without [[understanding]] existentiality it is impossible to cross the ocean of Sarp.sara by | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | exhausting our [[emotional]] reactions. Therefore, the special and prominent feature of the [[Mahayana path]] is the instrumentality of the two operational norms which [[manifest]] themselves to the prepared and serve as a protective guidance to [[sentient beings]] as long as | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sarp.sara lasts. Although the followers of the [[Paramitayana]] attend to an inner course that corre | ||

sponds to the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm by [[conceiving]] the [[nature]] of all that is as beyond the judgments of [[reason]] and as not [[existing]] in [[truth]], they have no such course as the one of [[Mantrayana]] which corresponds to the richness of operational modes. Therefore, because there is a great difference in the main feature of the [[path]], the [[realization]] of operational | sponds to the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] norm by [[conceiving]] the [[nature]] of all that is as beyond the judgments of [[reason]] and as not [[existing]] in [[truth]], they have no such course as the one of [[Mantrayana]] which corresponds to the richness of operational modes. Therefore, because there is a great difference in the main feature of the [[path]], the [[realization]] of operational | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

norms for the [[sake]] of others, there is the [[division]] into two courses. While | norms for the [[sake]] of others, there is the [[division]] into two courses. While | ||

| − | the [[division]] into [[Hinayana]] and [[Mahayana]] is due to the means employed and not because of a difference in the [[nature]] of [[intelligence]] through which [[no-thing-ness]] is apprehended, the [[division]] of the [[Mahayana]] into [[Paramitayana]] and [[Mantrayana]] also is not due to a difference in the discriminative acumen which [[understands]] the profound [[nature]] of all that is, but because of the [[techniques]] employed. The differentiating [[quality]] is the [[realization]] of operational norms, and the transfigurational technique which effects tpe [[realization]] of these norms is {{Wiki|superior}} to all other [[techniques]] used in the other courses". | + | the [[division]] into [[Hinayana]] and [[Mahayana]] is due to the means employed and not because of a difference in the [[nature]] of [[intelligence]] through which [[no-thing-ness]] is apprehended, the [[division]] of the [[Mahayana]] into [[Paramitayana]] and [[Mantrayana]] also is not due to a difference in the discriminative acumen which [[understands]] the profound [[nature]] of all that is, |

| + | |||

| + | but because of the [[techniques]] employed. The differentiating [[quality]] is the [[realization]] of operational norms, and the transfigurational technique which effects tpe [[realization]] of these norms is {{Wiki|superior}} to all other [[techniques]] used in the other courses". | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

From this it follows that the combination of [[Paramitayana]] and [[Mantrayana]] is more effective than any course pursued alone, although each course has its goal-achievement. This, too, has been stated by Tsongkha-pa 1 : | From this it follows that the combination of [[Paramitayana]] and [[Mantrayana]] is more effective than any course pursued alone, although each course has its goal-achievement. This, too, has been stated by Tsongkha-pa 1 : | ||

| − | ((It has been said that one is {{Wiki|liberated}} from Sa:rp.sara when one [[knows]] properly both the [[Mantrayana]] and [[Paramitayana]] [[methods]]. Common to both is the [[idea]] that, failing to understand the [[nature of mind]] as not [[existing]] as a [[self]], through the power of believing it to be a [[self]] all other [[emotional]] upsets are generated, and through them, in turn, [[karmic]] [[actions]] are performed, and because of these [[actions]] one roams about in Sa:rp.sara. Specific to the [[Anuttarayogatantra]] is the [[idea]] that motivity, which spreads from an [[indestructible]] {{Wiki|creativity}} centre in the region of the [[heart]] as a focal point of [[experience]], [[initiates]] emotively toned responses by which [[karmic]] [[actions]] are performed. If one does not know how this process comes into [[existence]], and finally recedes gradually into this centre, one is [[fettered]] in Sa:rp.sara. This means that, when regarding the common process of [[birth]] and [[death]] one has [[realized]] the necessity of finding that point of view which one intuitively apprehends the [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] of a [[self]], as explained by the [[Madhyamika philosophy]], one will become utterly | + | ((It has been said that one is {{Wiki|liberated}} from Sa:rp.sara when one [[knows]] properly both the [[Mantrayana]] and [[Paramitayana]] [[methods]]. Common to both is the [[idea]] that, failing to understand the [[nature of mind]] as not [[existing]] as a [[self]], through the power of believing it to be a [[self]] all other [[emotional]] upsets are generated, and through them, in turn, [[karmic]] [[actions]] |

| − | + | ||

| + | are performed, and because of these [[actions]] one roams about in Sa:rp.sara. Specific to the [[Anuttarayogatantra]] is the [[idea]] that motivity, which spreads from an [[indestructible]] {{Wiki|creativity}} centre in the region of the [[heart]] as a focal point of [[experience]], [[initiates]] emotively toned responses by which [[karmic]] [[actions]] are performed. If one does not know how this process | ||

| + | |||

| + | comes into [[existence]], and finally recedes gradually into this centre, one is [[fettered]] in Sa:rp.sara. This means that, when regarding the common process of [[birth]] and [[death]] one has [[realized]] the necessity of finding that point of view which one intuitively apprehends the [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] of a [[self]], as explained by the [[Madhyamika philosophy]], one will become utterly | ||

| − | have to be eliminated in addition. Yet it is the claim (of [[Mantrayana]]) that [[Buddhahood]] is found quickly, and not [[realized]] only after many [[aeons]] as it is stated in the ParamiUiyana works. When the emotively toned responses such as [[passion]], a version and others which [[fetter]] [[beings]] in Sarp.sara and which in the [[Paramitayana]] have been said to arise from the [[belief]] in a [[self]], have been abolished, their power has come to an end. This is because, though they have not been shown to arise from | + | convinced about the efficacy of this view which makes the round of [[birth]] and [[death]] ineffective. It also means that in regard |

| − | motility, motility aids them when they have come into [[existence]] by the [[belief]] in a [[self]] as the organizatory [[cause]]. Therefore, if one does not have the discriminative acumen which apprehends the [[non-existence]] of a [[self]], the real means to stop the organizatory power of the [[belief]] in a [[self]] which brings about Sa:rp.sara, one will not be able to become free from Sa:rp.sara, even if the generally aiding power of motility has been stopped. | + | to the specific process of [[birth]] and [[death]] one realizes the necessity of [[knowing]] the specific means to make ineffective motility, which [[initiates]] emotively toned responses. This [[latter]] method, however, is not necessary for merely becoming |

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|liberated}} from Sarpsara, because Srav akas and [[Pratyekabuddhas]] also find [[deliverance]] from Sarpsara, although they do not resort to this special method of [[Mantrayana]]. It is (commonly) claimed that it is not enough to eliminate overt [[emotional]] responses which [[cause]] one to roam about in Sa:rp.sara, but that all their latent potentialities | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | have to be eliminated in addition. Yet it is the claim (of [[Mantrayana]]) that [[Buddhahood]] is found quickly, and not [[realized]] only after many [[aeons]] as it is stated in the ParamiUiyana works. When the emotively toned responses such as [[passion]], a version and others which [[fetter]] [[beings]] in Sarp.sara and which in the [[Paramitayana]] have been said to arise from the [[belief]] in a [[self]], have | ||

| + | |||

| + | been abolished, their power has come to an end. This is because, though they have not been shown to arise from | ||

| + | motility, motility aids them when they have come into [[existence]] by the [[belief]] in a [[self]] as the organizatory [[cause]]. Therefore, if one does not have the discriminative acumen which apprehends the [[non-existence]] of a [[self]], the real means to stop the organizatory power of the [[belief]] in a [[self]] which brings about Sa:rp.sara, one will not be able to become free from Sa:rp.sara, even | ||

| + | |||

| + | if the generally aiding power of motility has been stopped. | ||

Hence both procedures are necessary. While the former method has the capacity to eliminate emotively toned responses completely, it does so more quickly when it combines with the [[latter]] method; hence [[Mantrayana]] is the quick [[path]]". | Hence both procedures are necessary. While the former method has the capacity to eliminate emotively toned responses completely, it does so more quickly when it combines with the [[latter]] method; hence [[Mantrayana]] is the quick [[path]]". | ||

| − | Two points deserve special notice. The one is the statement that [[Mantrayana]] is a quick method; the other is the specific {{Wiki|terminology}} of this [[discipline]] which deals with the same [[subject]] {{Wiki|matter}} as does the [[Paramitayana]]. The [[language]] of the Siitras, which are the basis of the [[Paramitayana]], is 'nominal' and propositional inasmuch as that which is stated can be apprehended intellectually with but incidental references to [[experience]]. What the Siitras say can be said again quite intelligibly | + | Two points deserve special notice. The one is the statement that [[Mantrayana]] is a quick method; the other is the specific |

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|terminology}} of this [[discipline]] which deals with the same [[subject]] {{Wiki|matter}} as does the [[Paramitayana]]. The [[language]] of the Siitras, which are the basis of the [[Paramitayana]], is 'nominal' and propositional inasmuch as that which is stated can be apprehended intellectually with but incidental references to [[experience]]. What the Siitras say can be said again quite intelligibly | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

without, however, having any [[concern]] in that to which it pertains. The [[language]] of [[Mantrayana]], on the other hand, attempts to express valuable [[experiences]], which are 'felt' [[knowledge]] rather than [[knowledge]] 'about' something. Following the {{Wiki|distinction}} by L. A. Reid , it is important | without, however, having any [[concern]] in that to which it pertains. The [[language]] of [[Mantrayana]], on the other hand, attempts to express valuable [[experiences]], which are 'felt' [[knowledge]] rather than [[knowledge]] 'about' something. Following the {{Wiki|distinction}} by L. A. Reid , it is important | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

always to be {{Wiki|aware}} that the [[language]] of [[Mantrayana]] is '[[embodying]]' | always to be {{Wiki|aware}} that the [[language]] of [[Mantrayana]] is '[[embodying]]' | ||

[[language]], while that of the [[Paramitayana]] is predominantly 'categorizing'. And as it is not immediately necessary to [[experience]] what the Siitras teach, they can be studied at arm's length (although they were never | [[language]], while that of the [[Paramitayana]] is predominantly 'categorizing'. And as it is not immediately necessary to [[experience]] what the Siitras teach, they can be studied at arm's length (although they were never | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

meant to be dealt with in such a way, to be discussed at {{Wiki|social}} gatherings where '[[interesting]]' [[people]] are inordinately puffed up with their [[own]] importance). It will readily be admitted that it will take a long, indeed, a very long time until one '[[feels]]' what it is all about. [[Mantrayana]], whl.ch is always 'felt' [[knowledge]], presupposes 'engagement' and therefore is immediate. But there lies the tremendous [[danger]] which is not [[realized]] | meant to be dealt with in such a way, to be discussed at {{Wiki|social}} gatherings where '[[interesting]]' [[people]] are inordinately puffed up with their [[own]] importance). It will readily be admitted that it will take a long, indeed, a very long time until one '[[feels]]' what it is all about. [[Mantrayana]], whl.ch is always 'felt' [[knowledge]], presupposes 'engagement' and therefore is immediate. But there lies the tremendous [[danger]] which is not [[realized]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

by those who [[crave]] for that which is labelled '[[Tantrism]]'. Unless properly prepared by first having developed one's [[intellectual]] acumen and having gained an unrestricted {{Wiki|perspective}}, which is a most gruelling process, there is no chance to realize the goal; [[insanity]] in its milder or more severe [[form]] has too often been the outcome for those who attempted a shortcut in [[spiritual development]]. While it is possible to gain an unrestricted {{Wiki|perspective}}, a '[[middle view]]', without pursuing the [[path]] of self-develop | by those who [[crave]] for that which is labelled '[[Tantrism]]'. Unless properly prepared by first having developed one's [[intellectual]] acumen and having gained an unrestricted {{Wiki|perspective}}, which is a most gruelling process, there is no chance to realize the goal; [[insanity]] in its milder or more severe [[form]] has too often been the outcome for those who attempted a shortcut in [[spiritual development]]. While it is possible to gain an unrestricted {{Wiki|perspective}}, a '[[middle view]]', without pursuing the [[path]] of self-develop | ||

| − | ment, [[Mantrayana]] is indissolubly connected with this [[path]] for which the {{Wiki|initiatory}} [[empowerment]] is a necessity. This is so because the | + | |

| − | + | ||

| + | ment, [[Mantrayana]] is indissolubly connected with this [[path]] for which the {{Wiki|initiatory}} [[empowerment]] is a necessity. This is so because the empowerment itself releases an experiental process which must be guarded by the strictest [[self-discipline]]. | ||

Although [[Mantrayana]] is the climax of [[Buddhist]] [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|culture}}, it remains in itself a graded process. This is evident from its [[division]] into [[Kriyatantra]], Caryatantra, [[Yogatantra]], and [[Anuttarayogatantra]]. | Although [[Mantrayana]] is the climax of [[Buddhist]] [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|culture}}, it remains in itself a graded process. This is evident from its [[division]] into [[Kriyatantra]], Caryatantra, [[Yogatantra]], and [[Anuttarayogatantra]]. | ||

| − | The [[word]] [[Tantra]] defies any attempt at translation, because it is too complex to be rendered adequately. It denotes all that is otherwise described as the ground, the [[path]], and the goal . As the ground it is the primal source from which everything takes its [[life]] and seems to lie beyond all that is [[empirical]] and [[objective]]. It is a {{Wiki|light}} by which one sees rather than that which one ses And in this [[illuminating]] [[character]] it is the ground against which everything [[objective]] stands revealed. It has no specific traits of its [[own]] and seems to be a vast {{Wiki|continuum}} out of which all specific entities are shaped. As the ground it is the self-conscious [[existence]] of the {{Wiki|individual}} who through this [[awareness]] is stirred to express himself in the {{Wiki|light}} of his possibilities. In so expressing himself he travels a [[path]] that is graded towards an apex. This travelling along the road of self-development is an unfolding of [[infinite]] riches, rather than a march from one point to another. Unhindered by {{Wiki|tendencies}} to consider goalachievement as a final [[state]], the goal remains an inspiring source. Since | + | |

| + | |||

| + | The [[word]] [[Tantra]] defies any attempt at translation, because it is too complex to be rendered adequately. It denotes all that is otherwise described as the ground, the [[path]], and the goal . As the ground it is the primal source from which everything takes its [[life]] and seems to lie beyond all that is [[empirical]] and [[objective]]. It is a {{Wiki|light}} by which one sees rather than that | ||

| + | |||

| + | which one ses And in this [[illuminating]] [[character]] it is the ground against which everything [[objective]] stands revealed. It has no specific traits of its [[own]] and seems to be a vast {{Wiki|continuum}} out of which all specific entities are shaped. As the ground it is the self-conscious [[existence]] of the {{Wiki|individual}} who through this [[awareness]] is stirred to express himself in the | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|light}} of his possibilities. In so expressing himself he travels a [[path]] that is graded towards an apex. This travelling along the road of self-development is an unfolding of [[infinite]] riches, rather than a march from one point to another. Unhindered by {{Wiki|tendencies}} to consider goalachievement as a final [[state]], the goal remains an inspiring source. Since | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

the ground is often called the [[cause]] and the goal the effect, in between which comes the [[path]], one is tempted to think of the causal situation as a linear succession of events. But such an [[idea]] is foreign to [[Mantrayana]] | the ground is often called the [[cause]] and the goal the effect, in between which comes the [[path]], one is tempted to think of the causal situation as a linear succession of events. But such an [[idea]] is foreign to [[Mantrayana]] | ||